Labs have some tough decisions to make now that the FDA has issued a final rule giving it authority to regulate LDTs. Labs offering LDTs prior to publication of the final rule on May 6 have three choices: 1) comply with the new FDA regs and keep their LDTs on inhouse test menus; 2) switch to an FDA-cleared test kit (if available); or 3) ignore the FDA regs and risk potential enforcement actions and fines. For expert advice on option 1 from regulatory attorney Christine Bump.

Christine Bump, a regulatory attorney at Penn Avenue Law & Policy (Washington, DC), has been guiding laboratories and test manufacturers through the FDA’s premarket clearance process and post market compliance requirements for 20 years. Below we summarize Bump’s

advice for keeping existing LDTs on the market.

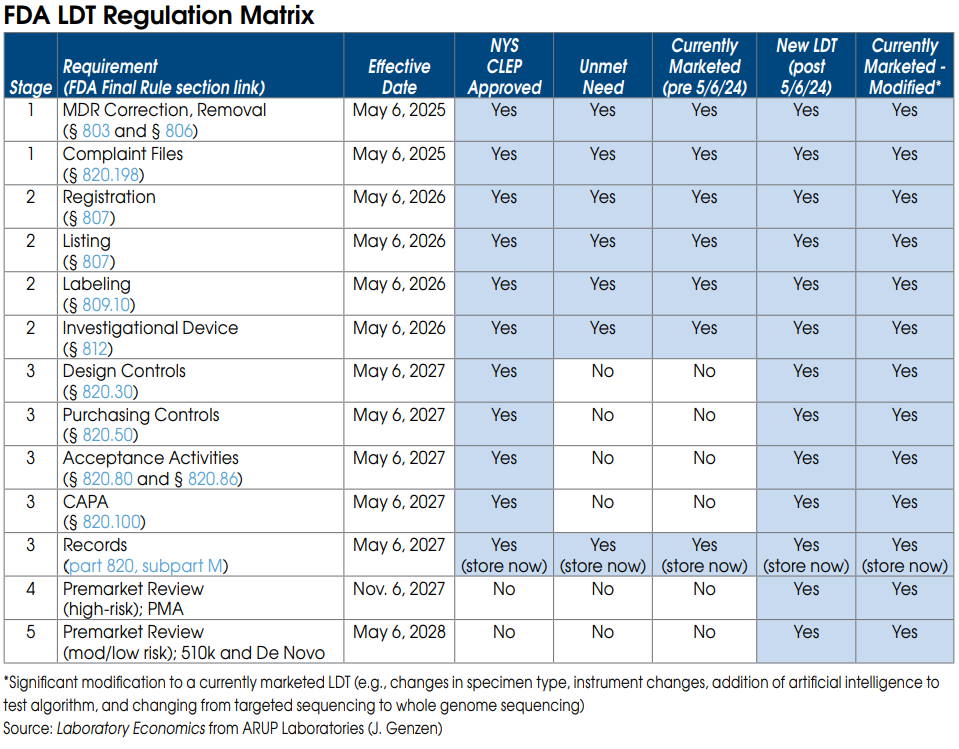

FDA Stage 1 requirements for currently marketed LDTs

Nearly all LDTs, including currently marketed LDTs (prior to May 6, 2024), “unmet need” LDTs performed by “integrated” health systems and NYS CLEP-approved tests, must meet Stage 1 requirements by May 6, 2025.

Stage 1 includes FDA Medical Device Reporting (MDR), which will require laboratories to report adverse events for any LDT that they perform. Under FDA’s regulations, an adverse event is any event that reasonably suggests that a device has or may have caused or contributed to a death or serious injury, or would be likely to cause or contribute to a death or serious injury if the event happens again. An adverse event report would therefore be required for an incorrect test result that has, may, or could cause such consequences. The incorrect test result could be caused by instrument malfunctions as well as mislabeled or contaminated specimens.

An adverse event report must generally be reported to the FDA within 30 days after the lab became aware of the error. The regulations require specific information be included in the report, and labs will also need to file\ a report that describes what corrective action they took, or if they chose to remove that LDT from their test menu.

An adverse event report could prompt the FDA to ask follow-up questions or schedule an on-site inspection.

The FDA is especially sensitive to incorrect test results that delayed patient treatment or caused

unnecessary treatment (or had the potential to do so).

Stage 1 also requires labs to maintain complaint files for each LDT they offer, including the date the complaint was received; the name, address, and phone number of the complainant; the nature and details of the complaint; any corrective action taken, etc. Specific records and reports

must also be maintained and submitted regarding corrections and removals of tests, including for

repairs, adjustments, relabeling, etc.

FDA Stage 2 requirements for currently marketed LDTs

Once again, Stage 2 requirements apply to nearly all LDTs and become effective May 6, 2026.

Stage 2 requires each laboratory to be registered with the FDA and list all of the LDTs they perform.

Stage 2 also requires labs to submit labeling for each LDT they offer. Labeling includes test performance information and a summary of supporting validation. As part of its review of labeling, the FDA plans to look closely at claims of superior performance and whether those claims are adequately substantiated. This includes any test claims made on a lab’s website, brochures or by sales reps.

Labeling information is typically included as a package insert or affixed to test kit box for FDA-cleared or approved IVD tests. However, since LDTs are not distributed in boxed test kits, it is unclear exactly where the label for an LDT will need to be placed. Labels might be required on the LDT test requisition form, but this hasn’t been confirmed yet. We’re waiting for the FDA to issue more guidance on label requirements.

FDA Stage 3 requirements for currently marketed LDTs

By May 6, 2027, currently marketed as well as “unmet need” LDTs developed and used within “integrated” health systems need to be in compliance with the records requirements of the quality system regulation. These records relate to the device master record, the device history record, and the quality system record. (Note: Complaint file record requirements are already covered under Stage 1.)

The device master records must include information about device specifications, production process specifications, quality assurance procedures and specifications, packaging and labeling specifications, and procedures and methods for installation, maintenance, and servicing.

The device history records must include information about the dates and quantity manufactured, the quantity released for distribution, acceptance records, information to identify each production unit and device identifiers.

Labs must have the required information compiled, documented, and in a records system that is accessible and readily available to FDA investigators during inspections.

FDA On-site Inspections

All registered lab facilities performing LDTs are subject to scheduled on-site inspections by the FDA every two years. FDA inspections are completely different than and are independent of CMS CLIA and CAP inspections. FDA inspectors will be focused on reviewing LDT test records and files. However, the reality is that the FDA already lacks the resources to perform regularly scheduled on-site inspections of existing test kit manufacturers. The agency may have difficulty keeping up with the thousands of new lab facilities that fall under its purview as a result of its final rule.